- Behcet's-related links, at http://www.bdshowonline.com

- Informational Behcet's site at www.behcetsdisease.com

- Blog at http://behcets.blogspot.com

- Yahoo groups; one named Bechets and the other Behcet-support

- http://www.bdchatroom.com

- BIG Website at: http://www.behcet.org.il

- ABDA website at: http://www.behcets.com

Blog changes

Thanks to everyone who followed Training Because I Can! over the last nine years. This blog started with Addison's Disease, hypothyroidism and a crazy idea of doing an Ironman distance triathlon. My life has changed and so has this blog. I am using this blog strictly for Addison's Support topics from here on out. I hope to continue providing people with hints for living life well with adrenal insufficiency.

Thursday, January 1, 2009

Off topic, Bechet's link update

Here are some Behcet's disease resources for anyone who is interested.

Happy 2009!

"No matter how well you know the course, no matter how well you may have done in a given race in the past, you never know for certain what lies ahead on the day you stand at the starting line waiting to test yourself once again. If you did know, it would not be a test; and there would be no reason for being there."

- Dan Baglione

Above is a great quote for the new year whether you do a sport or not. None of us knows what lies ahead. I hope everyone has a healthy and happy 2009!

Below is a slide show of Aspen Trail, my favorite trail around here. I took pictures each time I went there during 2008.

Sunday, December 28, 2008

Migraines, melatonin and sleep

In the last few days, I've come across some interesting migraine stuff that I've never researched before. It might be of interest to some of you migraine sufferers. It has to do with migraines, melatonin and sleep.

I saw a migraine specialist in Boulder, CO in September. During the course of the visit, he asked me if I had any trouble with my sleep. I quickly responded NO BUT and I listed off some problems that I never thought of as problems. I snore. I'm not the classic snorrer. I'm not overweight, don't have high blood pressure, etc. It seems that snoring and migraines can be related and snoring is a sleeping problem! Any way, with the discussion about sleep, I realized I DO have sleep problems that I will not bore you with.

Because I think my migraines are serotonin related, this month I doubled my L-Tyrosine (needed for the synthesis of serotonin) during the week when I usually get migraines. So far so good. No migraine to report. Interestingly, it turns out serotonin is needed to synthesize melatonin. Melatonin directly affects sleep.

We all get different headaches and migraines for different reasons. All the cures are different. We all can respond differently to the same supplements and medications. Do what you want with the information below. ASK A DOCTOR BEFORE MAKING ANY CHANGES TO YOUR MEDS!

Melatonin Decreases Migraine Frequency and Intensity

Laurie Barclay, MD

Medscape Medical News 2004. © 2004 Medscape

Medscape Medical News 2004. © 2004 Medscape

Sept. 9, 2004 — In chronic migraine sufferers, melatonin decreases headache frequency and intensity and reduces triptan consumption, according to the results of an open-label trial published in the Aug. 24 issue of Neurology.

"There is increasing evidence that melatonin secretion and pineal function are related to headache disorders," write M. F. P. Peres, MD PhD, from the Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein in São Paulo, Brazil, and colleagues. "Altered melatonin levels have been found in cluster headache, migraine with and without aura, menstrual migraine, and chronic migraine."

Of 40 patients with episodic migraine with or without aura meeting International Headache Society (IHS) diagnostic criteria who were screened during the baseline period, three patients did not have headaches during the baseline period, and three patients were lost to follow-up evaluation. Patients with chronic daily headache, insomnia, or considerable sleep hygiene problems were excluded, as were patients receiving preventive therapy three months before recruitment for the trial. Study participants averaged between two and eight migraine headaches per month.

Of 34 patients (29 women, five men) who started prophylactic treatment with melatonin (3 mg, 30 minutes before bedtime) 32 patients completed the four-month study, consisting of a one-month baseline period and a three-month therapy phase. During the study, participants completed a study diary, and they continued to take triptans, ergots, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and analgesics as needed.

Of 32 patients who completed the study, 25 patients (78.1%) had at least a 50% reduction in headache frequency from baseline, eight patients (25%) had no headaches, and none of the patients had increased headaches after three months of therapy. Reduction in frequency was greater than 75% in seven patients (21.8%), and 50% to 75% in 10 patients (31.3%).

Melatonin decreased mean headache frequency per month from 7.6 ± 3.2 at baseline to 4.4 ± 2.5 headaches at month one, and to 3.0 ± 3.1 headaches at month three (P < .001). On a 0-to-10 scale, mean headache intensity decreased from 7.4 ± 1.3 at baseline to 5.5 ± 1.9 at month one, and to 3.6 ± 2.7 at month three (P < .001). Mean headache duration in hours decreased from 19.8 ± 19.8 at baseline, to 10.2 ± 13.4 at month one, and to 8.8 ± 12.4 at month three (P < .001).

Patients reported significant clinical improvement by month one. Other benefits were decreases in overall analgesic and triptan consumption (P < .001) and in menstrually associated migraine. Three patients spontaneously reported increase in libido. Of two patients who withdrew from the study, one had excessive sleepiness and the other had alopecia. There were no significant changes in body weight.

"This is the first study to assess melatonin efficacy in migraine prevention," the authors write. "In our small series of migraine patients, melatonin was effective in reducing the number of headache days per month. A controlled study may be worthwhile."

Neurology. 2004;63:757

Reviewed by Gary D. Vogin, MD

"There is increasing evidence that melatonin secretion and pineal function are related to headache disorders," write M. F. P. Peres, MD PhD, from the Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein in São Paulo, Brazil, and colleagues. "Altered melatonin levels have been found in cluster headache, migraine with and without aura, menstrual migraine, and chronic migraine."

Of 40 patients with episodic migraine with or without aura meeting International Headache Society (IHS) diagnostic criteria who were screened during the baseline period, three patients did not have headaches during the baseline period, and three patients were lost to follow-up evaluation. Patients with chronic daily headache, insomnia, or considerable sleep hygiene problems were excluded, as were patients receiving preventive therapy three months before recruitment for the trial. Study participants averaged between two and eight migraine headaches per month.

Of 34 patients (29 women, five men) who started prophylactic treatment with melatonin (3 mg, 30 minutes before bedtime) 32 patients completed the four-month study, consisting of a one-month baseline period and a three-month therapy phase. During the study, participants completed a study diary, and they continued to take triptans, ergots, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and analgesics as needed.

Of 32 patients who completed the study, 25 patients (78.1%) had at least a 50% reduction in headache frequency from baseline, eight patients (25%) had no headaches, and none of the patients had increased headaches after three months of therapy. Reduction in frequency was greater than 75% in seven patients (21.8%), and 50% to 75% in 10 patients (31.3%).

Melatonin decreased mean headache frequency per month from 7.6 ± 3.2 at baseline to 4.4 ± 2.5 headaches at month one, and to 3.0 ± 3.1 headaches at month three (P < .001). On a 0-to-10 scale, mean headache intensity decreased from 7.4 ± 1.3 at baseline to 5.5 ± 1.9 at month one, and to 3.6 ± 2.7 at month three (P < .001). Mean headache duration in hours decreased from 19.8 ± 19.8 at baseline, to 10.2 ± 13.4 at month one, and to 8.8 ± 12.4 at month three (P < .001).

Patients reported significant clinical improvement by month one. Other benefits were decreases in overall analgesic and triptan consumption (P < .001) and in menstrually associated migraine. Three patients spontaneously reported increase in libido. Of two patients who withdrew from the study, one had excessive sleepiness and the other had alopecia. There were no significant changes in body weight.

"This is the first study to assess melatonin efficacy in migraine prevention," the authors write. "In our small series of migraine patients, melatonin was effective in reducing the number of headache days per month. A controlled study may be worthwhile."

Neurology. 2004;63:757

Reviewed by Gary D. Vogin, MD

To Print: Click your browser's PRINT button.

NOTE: To view the article with Web enhancements, go to:

http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/549904

Headache and Sleep Disorders: Review and Clinical Implications for Headache Management

Jeanetta C. Rains, PhD; J. Steven Poceta, MD

Headache. 2006;46(9):1344-1363. ©2006 Blackwell Publishing

Posted 01/11/2007

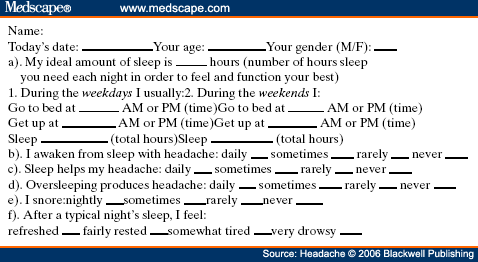

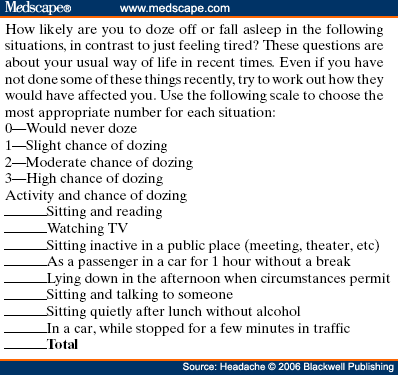

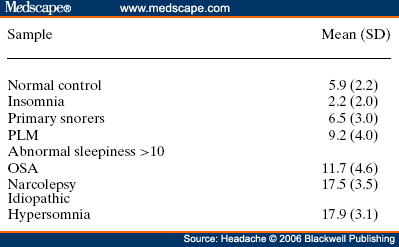

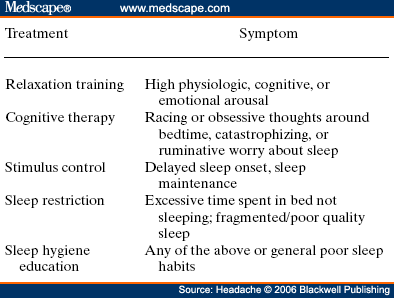

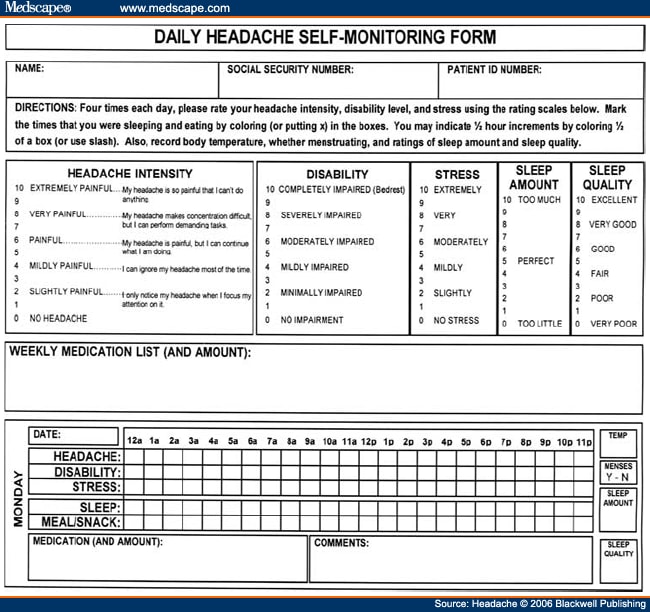

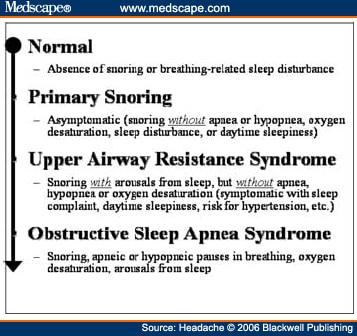

Abstract and IntroductionAbstractReview of epidemiological and clinical studies suggests that sleep disorders are disproportionately observed in specific headache diagnoses (eg, migraine, tension-type, cluster) and other nonspecific headache patterns (ie, chronic daily headache, "awakening" or morning headache). Interestingly, the sleep disorders associated with headache are of varied types, including obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), periodic limb movement disorder, circadian rhythm disorder, insomnia, and hypersomnia. Headache, particularly morning headache and chronic headache, may be consequent to, or aggravated by, a sleep disorder, and management of the sleep disorder may improve or resolve the headache. Sleep-disordered breathing is the best example of this relationship. Insomnia is the sleep disorder most often cited by clinical headache populations. Depression and anxiety are comorbid with both headache and sleep disorders (especially insomnia) and consideration of the full headache-sleep-affective symptom constellation may yield opportunities to maximize treatment. This paper reviews the comorbidity of headache and sleep disorders (including coexisting psychiatric symptoms where available). Clinical implications for headache evaluation are presented. Sleep screening strategies conducive to headache practice are described. Consideration of the spectrum of sleep-disordered breathing is encouraged in the headache population, including awareness of potential upper airway resistance syndrome in headache patients lacking traditional risk factors for OSA. Pharmacologic and behavioral sleep regulation strategies are offered that are also compatible with treatment of primary headache.IntroductionSleep disorders occur disproportionately among headache patients, and both headache and sleep disorders are associated with significant psychiatric comorbidity. As described below, sleep disorders are disproportionately observed in specific headache diagnostic groups (ie, migraine, tension-type, cluster) and other headache patterns (ie, chronic daily headache, "awakening" or morning headache) irrespective of diagnosis. Interestingly, those sleep disorders associated with headache are varied in nature including breathing, movement, and circadian rhythm disorders as well as insomnia. In the absence of a sleep disorder, variations in sleep duration and schedule (oversleeping or undersleeping) are commonly identified headache triggers. These associations between sleep and headache are diverse in nature, but common to all is the dysregulation of sleep processes apparently impacting headache threshold.Similar psychiatric disorders are comorbid with both headache and sleep disorders. As detailed elsewhere in this volume and the accompanying Headache journal supplement devoted to Psychiatric Comorbidity,[1-6] affective disorders occur with at least 3-fold greater frequency in migraineurs than that in the general population, and the prevalence increases in clinical populations, especially with chronic daily headache.[7] Sleep disturbance (increased or decreased sleep) is a diagnostic symptom of a number of psychiatric disorders,[8] and occurs in the majority of patients with depression, anxiety, and chemical dependencies.[9-11] Most often the sleep complaint is "insomnia" but the complaint of "hypersomnia" occurs as well. Sleep disturbance is believed to be an important precipitating or premonitory symptom of affective disorders, because prospective longitudinal studies have observed sleep disturbance to precede and predict the onset of later psychiatric symptoms by years.[12-14] The association of headache, sleep, and psychiatric disorders likely stems from related pathogenic processes.[15] Consideration of the full headache-sleep-affective symptom constellation may yield opportunities to impact headache threshold and maximize treatment. The process for the regulation of sleep in headache management includes: identification and treatment of primary sleep disorders, management of insomnia with or without concurrent affective illness, and optimizing the schedule, duration, and quality of sleep. This paper reviews the nature and magnitude of comorbidity between headache and sleep disorders through relevant epidemiological and clinical prevalence studies (including psychiatric symptoms where available), clinical implications for headache evaluation, sleep screening strategies, identification of primary sleep disorders, and behavioral sleep regulation strategies for the primary headache patient. Headache and Sleep Disorders ComorbidityNo epidemiological studies to date have examined the comorbidity of headache (by specific International Headache Society diagnoses[16]) and the complete spectrum of sleep disorders in the general population. However, several relevant studies have examined one or more aspects of the headache-sleep comorbidity spectrum.Epidemiological StudiesAmong available studies, Ohayon[17] provided data on the broadest range of sleep disorders, reporting findings of a European study of 18,980 telephone interviews estimating the prevalence of "chronic morning headache" to be 7.6% (with chronic morning headache characterized as occurring "daily," "often," or "sometimes"). Prevalence rates were higher among women than men (8.4% vs. 6.7%). More individuals with morning headache than individuals without headache reported sleep complaints including insomnia (odds ratio [OR]: 2.1), circadian rhythm disorder (1.97), loud snoring (1.42), sleep-related breathing disorder (1.51), nightmares (1.39), and other dyssomnia (2.30). When the data were reanalyzed in a model that only used information obtained from individuals with "daily" morning headache, ORs were greater for all sleep disorders except insomnia. Relationships were also identified between headache and major depression alone (2.70), anxiety alone (1.98), and the combination of both "depression and anxiety disorders" (3.51). Heavy alcohol use was also associated with morning headache (1.83). Morning headaches were not associated with caffeine use, as those who did not drink coffee exhibited greater morning headache than those who drank at least 1 cup per day, arguing against the hypothesis that morning headache was attributable to caffeine withdrawal among this large sample.Among available studies, Ohayon[17] provided data on the broadest range of sleep disorders, reporting findings of a European study of 18,980 telephone interviews estimating the prevalence of "chronic morning headache" to be 7.6% (with chronic morning headache characterized as occurring "daily," "often," or "sometimes"). Prevalence rates were higher among women than men (8.4% vs. 6.7%). More individuals with morning headache than individuals without headache reported sleep complaints including insomnia (odds ratio [OR]: 2.1), circadian rhythm disorder (1.97), loud snoring (1.42), sleep-related breathing disorder (1.51), nightmares (1.39), and other dyssomnia (2.30). When the data were reanalyzed in a model that only used information obtained from individuals with "daily" morning headache, ORs were greater for all sleep disorders except insomnia. Relationships were also identified between headache and major depression alone (2.70), anxiety alone (1.98), and the combination of both "depression and anxiety disorders" (3.51). Heavy alcohol use was also associated with morning headache (1.83). Morning headaches were not associated with caffeine use, as those who did not drink coffee exhibited greater morning headache than those who drank at least 1 cup per day, arguing against the hypothesis that morning headache was attributable to caffeine withdrawal among this large sample. Large cross-sectional epidemiological studies of headache have addressed aspects of sleep. Boardman et al[18] identified relationships between headache severity, sleep problems (ie, trouble falling asleep, wake up several times, trouble staying asleep, or waking after usual amount of sleep feeling tired or worn out), and affective disorders; headache frequency was associated with slight (OR: 2.4), moderate (3.6), and severe (7.5) sleep complaints, as well as with anxiety (4.1) and depression (1.7). Rasmussen[19] examined the prevalence of sleep complaints among persons with migraine and tension-type headache relative to the general population. Sleep complaints were more common among tension-type than migraine headache patients and the population at large. Nonrefreshing sleep was associated with migraine for both males and females, and with tension-type headache among females. Snoring was associated with migraine in women only. Onset of headache usually occurred during sleep or upon awakening for 24% of migraineurs and 12% of tension headache, with morning headache occurring more commonly among individuals having migraine than tension headache. Snoring has been widely examined as a sensitive though not specific indicator for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in epidemiological research. A large cross-sectional study of Danish middle-aged and elderly males identified a strong statistical relationship between snoring and nonspecific headache (ie, any form of headache).[20] Considering both females and males, a Swedish study combining epidemiological and sleep clinic data[21] reported that headache occurred more commonly among patients with heavy snoring and with sleep apnea than among the general population. Morning headache in particular was reported by 18% of snorers and apneics versus only 5% of controls. In a case-control epidemiological survey conducted within the United States, Scher et al[22] compared the prevalence of snoring in a group of chronic daily headache patients (n = 206) to a group of episodic headache patients (n = 507). Habitual snoring was more common among chronic daily than among episodic headache patients (24% vs. 14%, respectively); authors noted that the association to snoring was independent of weight, age, gender, hypertension, and other sleep disturbances (eg, caffeine). Conversely, in Australia, Olson et al[23] found that morning headaches were not related to apneics (based on questionnaire and respiratory home monitoring) compared to snorers (OR: 0.2) or non-snorers (0.1). Clinical StudiesResearch drawing from headache patients and sleep-disordered patients provides evidence of the nature and clinical relevance of the headache-sleep comorbidity among these respective populations.Headache Patient Populations. Sleep disorders and sleep complaints are prevalent among headache patients. This evidence is derived from descriptive studies (with and without comparison groups as controls), and (though rarely) studies utilizing objective polysomnography to assess sleep. The largest clinical study published to date reported the prevalence of sleep complaints obtained from 1283 migraineurs presenting for headache treatment.[24] Within this migraine population, sleep disturbance and oversleeping were recognized as headache precipitants (ie, headache triggers) by 50% and 37% of patients, respectively, while 85% reported sleeping as a means to relieve headache. Many patients reported difficulty initiating sleep (53%) and maintaining sleep (61%) at least occasionally. Morning headaches were reported by 71% of migraineurs. Though insomnia was not systematically assessed, chronically shortened sleep patterns similar to those characteristics of insomnia were observed in 38% of migraineurs (sleeping on an average ≤6 hours per night). Shortened sleep patterns were associated with more frequent and more severe migraine. In a clinical sample of 289 headache patients, insomnia was identified in 60% and fatigue in 73% patients, with insomnia more common among patients with chronic versus episodic headache.[25] Paiva et al[26] described sleep-related headache in 28 of 50 consecutive headache patients, with the large majority of patients reporting difficulty initiating (82.1%) and maintaining sleep (92.9%). The average nightly sleep duration for the entire sample was only 5.6 hours. Likewise, Rothrock et al[27] identified a greater prevalence of insomnia among chronic (57/132) versus episodic (46/243) headache patients. Notably, historic or current history of depression did not differ among the groups. Relative to an age- and gender-matched comparison group (less than 1 headache per month), Spierings and van Hoof[28] found headache patients presenting for specialty treatment slept significantly shorter durations (6.7 vs. 7.0 hours), reported more difficulty initiating sleep (31.4 vs. 21.1 minutes), and took longer to fall back asleep after awakenings during the night (28.5 vs. 14.6 minutes). The study also observed that as a group, only women with headache experienced fatigue of greater intensity than gender-matched controls, whereas men with headache reported more difficulty initiating sleep and falling back asleep after awakenings than controls. Though much less is known about pediatric than adult sleep-related headache, one study observed significantly higher prevalence of insomnia, narcolepsy, and excessive daytime sleepiness among children with headache in a pediatric neurology clinic than in age- and sex-matched non-headache controls within the clinic.[29] However, the study did not observe a higher prevalence of sleep apnea, restlessness, and parasomnias among pediatric headache patients. Paiva et al[30] reported results of polysomnography from 25 headache clinic patients complaining of morning headache. Sleep disorders were diagnosed in 13 of 25 patients, including OSA, periodic limb movements (PLMs), and fibrositis. In an extension of this research,[31] 17% of headache clinic patients (49 of 288 patients) reported that headaches were sleep-related in at least 75% of headache episodes. Polysomnography revealed the presence of a primary sleep disorder (OSA, PLMs, fibrositis, and psychophysiological insomnia) in 53% of the 49 patients with sleep-related headache in contrast with only 9% of the total sample. With the exception of the cases with PLMs (n = 8), treatment of the primary sleep disorder resolved headache. Cluster headache has been linked to sleep disorders. A study of 37 cluster headache patients who underwent polysomnography identified an 8.4-fold increase in the incidence of OSA relative to age- and gender-matched controls (58% vs. 14%, respectively) and this risk increased over 24-fold among patients with a body mass index (BMI) >25.[32] Another uncontrolled study of 31 cluster headache patients who underwent polysomnography observed OSA in 80% (25/31) of these patients.[33] A marked increase in the incidence of sleep-disordered breathing had been noted in earlier research,[34,35] and treatment of sleep apnea had been observed to improve cluster headache control.[34,36] Thus, available evidence indicates a marked increased incidence of sleep-disordered breathing among cluster patients,[34,35] and suggests that treatment of the apnea can improve this form of headache.[34,36] Headache may be precipitated, or "triggered," by dysregulation of sleep patterns. Among patients with migraine and tension-type headache, changes in sleep patterns (eg, sleep disturbance, sleep loss, oversleeping) routinely are listed among the most commonly observed precipitants of headache.[18,24-26,37-41] Sleep-Disordered Patient Populations. This review identified only a single published study that examined the prevalence of headache in sleep-disordered patients representing the full range of sleep disorders. Goder et al[42] examined morning headaches in 432 sleep clinic patients who underwent polysomnography and 30 healthy controls. Polysomnographic recordings from nights preceding morning headache were compared with nights without subsequent headache. Patients with sleep disorders reported significantly more headaches than healthy controls (34% vs. 7%). The study proceeded to examine the specific occurrence of tension-type headache the morning after polysomnographic recordings. Patients with migraine and other headaches that occurred during the night were not included because the authors wished to exclude the direct adverse influence of pain on sleep architecture. Twenty-five percent (108/432) of sleep-disordered patients reported morning tension-type headache within 30 minutes of waking compared to only 3% of controls. Any headache versus the specific description of "morning headache after polysomnography," respectively, occurred in 27% versus 22% of patients with sleep breathing disorders, 28% versus 26% with insomnia, 22% versus 19% with restless legs, 50% versus 38% with hypersomnia, 22% versus 15% with parasomnias, and finally 46% versus 16% with other sleep disorders. The occurrence of morning headache in the sleep laboratory was associated with a decrease in total sleep time, sleep efficiency, and amount of rapid eye movement sleep and with an increase in the wake-time during the preceding night, leading the authors to conclude that morning headaches in patients with sleep disorders might be associated with particular disturbances of the preceding night's sleep. Headache has not commonly been described among sleep-disordered patients except specifically in relation to sleep-disordered breathing. Headache (not otherwise specified) in relation to OSA has been examined in a number of studies with the occurrence of headache within this population varying widely from 15% to 60%.[43-46] Morning headache, though common among sleep disorders, appears most strongly associated with sleep apnea. Headache of any diurnal pattern was reported by 49% of apneics and 48% of insomniacs in the sleep clinic patient population, while "morning headaches" were significantly more common among apneics (74%) than among insomnias (40%).[47] Morning headache apparently may present as migraine, tension, cluster, or nonspecific other,[47] and often resolves or improves following treatment of sleep apnea with noninvasive positive pressure ventilation treatment or surgical modification of the upper airway to improve breathing.[31,34,36,45-49] Interestingly, a recent study identified persistent morning headache as the best predictor of persistent apnea in a sample of patients compliant but insufficiently treated with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP).[50] SummaryEpidemiological and clinical studies suggest that sleep disorders and complaints are disproportionately observed in specific headache diagnoses (eg, migraine, tension-type, cluster) and other nonspecific headache patterns (ie, chronic daily headache, "awakening" or morning headache). Depression and anxiety have also been associated with chronic headache when assessed in these epidemiological data. Interestingly, those sleep disorders associated with headache are varied in nature (ie, snoring, OSA, PLMs, circadian rhythm disorders, hypersomnia, and insomnia). These data are necessarily correlative in nature and do not address causality. However, findings are consistent with a hypothesis that headache, particularly morning headache and chronic headache, may be consequent to a sleep disorder—with the case most often examined in relation to sleep-disordered breathing. Insomnia is the sleep disorder most often cited among clinical headache populations, and acute sleep disturbance is identified as a common acute headache trigger.Clinical ImplicationsWhile there are no empirically established algorithms to guide clinical practice, there are now at least a few empirically supported tenets. The review suggests: (1) chronic daily headache, and especially "morning headache," is a particular, though nonspecific, indicator for sleep disorders; (2) the identification and management of a primary sleep disorder in the presence of headache may improve or resolve the headache (headache secondary to primary sleep disorder); (3) headache patients exhibit a high incidence of sleep disturbance which might trigger or exacerbate headache; and (4) such primary headache may improve with regulation of sleep. These findings argue for screening and management of sleep disturbance among headache patients.Screening for Sleep Disorders in Patients with HeadacheFor headache practitioners, several sources have emphasized the merits of a thorough clinical interview examining the headache pattern and history in relation to the sleep/wake cycle.[30,51-54] When headache occurs daily or is frequently present during sleep or upon awakening, it is particularly prudent to screen for the presence of a sleep anomaly.A careful sleep history can provide pertinent information that is often not addressed in the standard headache history. Of interest are the timing of sleep and wake, habits (eg, reading or television in bed, "hitting the snooze"), presleep routine, sleep environment, a description of the sleep period itself, daytime alertness versus sleepiness, and any special measures to promote sleep or wake. Useful information may be obtained not only from the patient, but also from the bed partner or other observer when possible. Patients who complain primarily of insomnia should especially be questioned about behavioral factors. Factors impacting on sleep include: (1) a bedroom environment that is not conducive to sleep (ie, light, noise, television, or other stimulation, a space utilized for nonsleep-promoting activities); (2) an irregular sleep schedule; and (3) drug effects (eg, alcohol, caffeine, and nicotine). A brief questionnaire is provided which is used in the author's (JSP) headache center to screen patients for sleep disorders ( Table 1 ). Sleep History. This questionnaire documents the most important aspects of the sleep history in a headache evaluation, illustrating sleep times, variability from weekday to weekend, the association of sleep with headaches, and the presence of snoring. The majority of patients with sleep disorders have sleepiness or otherwise impaired daytime cognitive function, and the questionnaire is administered along with the Epworth Sleepiness Scale[55] (ESS, Table 2 ). Standardized Questionnaires. The ESS has been validated against objective polysomnographic measures of the propensity to fall asleep and is probably the most widely used paper and pencil assessment tool to measure sleepiness. Patients complete the scale as a brief quantitative (but subjective) measure of sleepiness. Patient ratings are summed and scores can be compared to normative data collected on individuals with various sleep disorders and normal controls ( Table 3 ). Essentially, a score of less than 10 can be considered normal (although 2 to 5 is probably desirable), 10 to 15 moderate sleepiness, and 16 to 24 severe sleepiness. A wide variety of other questionnaires are available to assess sleep disorders, sleep quality, daytime sleepiness, sleep-related psychosocial functioning, impairment, and quality of life. Questionnaires vary in level of psychometric development, and are reviewed elsewhere.[56,57] Mnemonics. In adults, simple screening questions can direct the sleep history to identify patients "at risk" for sleep disorders. Inquiring about the Restorative nature of the patient's sleep, Excessive daytime sleepiness, tiredness or fatigue, the presence of habitual Snoring, and whether the Total sleep time is sufficient can be revealing. The mnemonics REST can help the clinician remember these four key questions in the screening history. A similar mnemonic had been developed and validated in pediatric screening for sleep disorders—the BEARSapproach[58] queries Bedtime sleep problems, Excessive daytime sleepiness, Awakenings at night, Regularity of sleep, and Snoring and breathing problems. Sleep Diary. The sleep diary, including paper and pencil and electronic recording devices, is probably the most commonly used systematic self-report tools for sleep assessment. With once a day monitoring, subjective estimates can be obtained over time of the regularity, duration, and quality of sleep. Monitoring can also include other specific variables that are potentially related to sleep, such as headache (combined headache/sleep diary). Figure 1 includes a headache diary structured to identify sleep patterns and disturbance as well as a wide range of other common headache triggers (Appendix includes diary and patient instructions). The diary yields information concerning regularity of the sleep/wake cycle, disorders of sleep onset and maintenance, total sleep time relative to time in bed (ie, sleep efficiency), napping, etc.  Figure 1. Sleep-Disordered BreathingSleep-disordered breathing is the general term referring to abnormalities of the respiratory pattern or the quality of ventilation during sleep. Alterations in respiration may be secondary to upper airway obstruction (OSA or hypopnea), loss of ventilatory effort (central sleep apnea), or both (mixed sleep apnea). OSA is characterized by the repetitive collapse (apnea) or partial collapse (hypopnea) of the pharyngeal airway during sleep usually terminated by resuscitative arousals from sleep that resume ventilation. Consequences of sleep-disordered breathing include nocturnal sleep disturbance, daytime somnolence, and diminished neurocognitive functioning. Recurrent arousals in association with intermittent hypoxia and hypercapnia have been implicated in cardiovascular disease,[59-61] insulin resistance, and other components of the metabolic syndrome.[62]Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Because of prevalence, the established association to headache, and the potential for headache to improve with treatment, OSA syndrome is the most important sleep-related breathing abnormality for consideration.[31,34,36,45,46,48,49] Intervention is warranted to aid in headache management as well as to avert the significant morbidity and mortality associated with sleep apnea.[63] Clinical symptoms and risk factors[64-66] for OSA are presented in Table 4 . An overweight headache patient (BMI ≥ 25) awakening with headache should particularly be questioned about snoring and other symptoms of sleep apnea.[32] Clinical tools have been developed to assist in screening and prediction for OSA using only clinical data.[67] For example, Berlin Sleep Questionnaire identified high- versus low-risk patients for OSA in the primary care environment (sensitivity 86%, specificity 77%, positive predictive value 89%, likelihood ratio 3.79) based on patient's neck circumference, presence of habitual snoring or apnea, and history of hypertension (Fig. 2).[68] While such tools alone are insufficient to rule in or rule out the condition, they may be useful in the clinical decision-making process.  Figure 2. Snoring and Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome. While most sleep-disordered breathing research to date has focused on OSA/hypopnea, a broader spectrum of abnormal breathing is now recognized as clinically meaningful. The spectrum of sleep-disordered breathing includes not only OSA but also snoring and upper airway resistance syndrome (UARS; Fig. 3).[69,70] In addition to apneas (cessation of airflow of ≥10 seconds duration) and hypopneas (>30% decrease in airflow for ≥10 seconds duration and with ≥4% oxygen desaturation), it is necessary to consider respiratory effort related arousals (RERAs). These are arousals in sleep resulting from increased upper airway resistance but not meeting criteria for apnea or hypopnea.  Figure 3. Snoring, empirically linked to chronic headache, is essentially vibration of the pharyngeal walls and implies airway resistance. At relatively low levels of airway resistance, snoring may not be associated with sleep disturbance or daytime impairment (asymptomatic snoring). As resistance increases, the inspiratory effort required to maintain ventilation rises to the point that transient arousals from sleep occur, even in the absence of oxygen desaturation. This pattern of repeated RERAs on polysomnography has been termed "upper airway resistance syndrome" or UARS.[71] UARS is associated with symptoms of sleep disturbance (eg, arousals and awakenings), daytime sleepiness or fatigue, and increased risk for hypertension.[72] While obstructive apnea and hypopnea syndrome is associated with a local neurologic impairment that is responsible for the occurrence of the hypopneas and apneas, patients with UARS have intact local neurologic systems and have the ability to respond to minor changes in upper airway dimension and resistance to airflow—leading to cyclic arousals from sleep and daytime sequela.[69,72] Patients with UARS differ from OSA patients in that UARS is associated with all ages, has a 1:1 male-to-female gender ratio, normal body habitus, lower blood pressure, and presents with insomnia greater than hypersomnia.[69] Individuals with UARS are believed to seek treatment for a variety of functional somatic complaints such as fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, and headache more often than for sleep complaints.[69] A recent study by Gold et al[73] examined such somatic complaints among individuals with UARS versus mild-to-moderate and moderate-to-severe OSA; over 50% of UARS patients exhibited headache compared to <30 style="font-size: 0.85em;">[22,74] and may well represent the manifestation of UARS, although this hypothesis has never been tested. Regardless, snorers with awakening headache, or with complaints of sleep or daytime functioning, raise suspicion and warrant investigation for sleep-disordered breathing.  Figure 4. Management of Sleep-Disordered Breathing. Identification and treatment of OSA is crucial not only for optimal head pain management but also for improving overall medical status such as improving blood pressure control.[75,76] Generally, referral for polysomnographic evaluation is needed to confirm the diagnosis and initiate appropriate treatment. Reevaluation of the headache syndrome following treatment of OSA is desirable, and may allow for other options in headache management since the potential trigger from the sleep disorder is now gone. As noted earlier, headache related to sleep-disordered breathing may present as tension-type, migraine, cluster, mostly morning, or other nonspecific headaches.[47] Primary treatments for OSA and UARS include weight loss, treatment of nasal allergies, positional treatment for supine-related apnea, upper airway surgery, dental devices, and nasal CPAP.[77] CPAP is the standard of care because of efficacy and the benign side effect profile, and is generally covered by all insurance plans after documentation of the diagnosis.[78] Treatment of headache that persists after resolution of sleep-disordered breathing depends on the exact headache diagnosis, but standard headache therapy recommendations apply. It is prudent to avoid sedation with hypnotics or opiates until the breathing is treated adequately, but after treatment, hypnotic-sedatives for insomnia can be considered. InsomniaInsomnia is the sleep complaint most often identified in clinical headache populations, as reviewed earlier. Insomnia is characterized by difficulty falling asleep (sleep onset disturbance), difficulty staying asleep (sleep maintenance disturbance), or awakening to early (sleep-offset) leading to impairment of next-day functioning, including psychological distress.[79] Insomnia can be primary (idiopathic) or a symptom of another disorder such as depression, chronic pain, or restless legs syndrome. That is, the complaint of insomnia should first be considered a symptom, and then a differential diagnosis considered. When specific causes of the insomnia are either ruled out or treated, primary insomnia as a diagnosis generally involves a condition of hypervigilance or hyperarousal with diminished ability to sleep. There is evidence for abnormal activation in certain central nervous system measures as well as in the hypothalamic-pituitary system.[80,81]Patients with primary insomnia describe difficulty falling sleep initially or difficulty returning to sleep when they awaken in the night, associated with daytime complaints of feeling nonrestored, fatigued, or tired. They are not generally hypersomnolent or excessively sleepy in the manner that is typical of individuals with disturbed sleep secondary to OSA, for example, consistent with the concept of an overall hyperarousal state. The causes are thought to usually involve an underlying predisposition to insomnia, then becoming chronic due to maladaptive behaviors that contribute to negative conditioning regarding relaxation and falling asleep. Pharmacologic Insomnia Treatment. Patients with headache who also have frequent or chronic primary insomnia may benefit from specific treatment with a hypnotic-sedative. Clinicians have many choices to treat insomnia after specific sleep disorders, such as OSA, have been treated or ruled out. There are several new treatments in the U.S. market for insomnia. The newest agents approved are non-benzodiazepine benzodiazepine receptor agonists (eszopiclone/Lunesta, zaleplon/Sonata, and zolpidem/Ambien and Ambien CR). Ramelteon/Rozerem is a recently available agent which does not have an effect on the benzodiazepine receptor. This drug is a melatonin receptor agonist, with action on the MT1 and MT2 receptor. Because of the possible benefit of melatonin in migraine and cluster prevention (see below), this agent has potential but is not yet studied for headache to our knowledge. The benzodiazepine hypnotics such as triazolam/Halcion and temazepam/Restoril remain available for treatment of insomnia. Antidepressants with sedative properties such as amitriptyline/Elavil or trazodone/Desyrel may provide benefit from several mechanisms besides sleep enhancement. Lastly, the newer anticonvulsants, often known as neuronal membrane stabilizing agents because of their broad applications, have potential to help various sleep disorders, such as restless legs syndrome[82] and various parasomnias.[83] Although insomnia and headache occur together more often than chance alone, there is no good understanding of cause and effect. For example, there are little or no data to demonstrate that treating insomnia in headache patients actually helps to relieve headache, although this is an occasional clinical experience. This possibility must be balanced against the risks, including dependency and tolerance, risk of falls, cognitive problems, and other known adverse effects. Nonetheless, it is reasonable to specifically evaluate and treat insomnia if present in a patient with headache. Some of these agents may be more appropriate for chronic use than others, but intermittent dosing (2 to 5 times per week) is usually desirable. The prescription to take a hypnotic-sedative occasionally can be an effective means of aborting a negative cycle of stress or other headache triggers (eg, menstruation) which might otherwise lead to migraine. Hypnotic-sedatives may also cause headache. The manufacturers' package insert information show that Ambien CR trials provoked headache 14% (placebo 11%) to 19% (16%); Lunesta 21% (placebo 13%) and 15% (placebo 14%); and Rozerem 7% (placebo 7%). Because these agents have little or no anti-anxiety effect or muscle-relaxant effect, if they help to relieve headache, the mechanism may be more specific to sleep improvement than less specific medications. Thus, clinical trials to assess the effect of treating insomnia specifically in patients with headache would provide needed clinical guidance. Behavioral Insomnia Treatment. Behavioral sleep treatments alone or in combination with pharmacologic treatments have demonstrated efficacy comparable or superior to hypnotic medications in the short-[84] and long-term[85,86] treatment of chronic insomnia and are recommended for insomnia comorbid with headache. Sleep diaries or sleep/headache diaries (Fig. 1) can be highly informative for patients and clinicians in defining the insomnia pattern (eg, sleep onset vs. maintenance insomnia; temporal patterns), behavior patterns interfering with sleep (eg, alerting behaviors in the sleep environment, worry), or diminishing sleep drive (eg, excessive amounts of time in bed not sleeping, daytime napping). Associations may be identified to other factors such as stress, mood, and diet, when comprehensive diaries are used (such as Fig. 1 with Appendix for patient instructions). Diary information can assist in identifying the optimal behavioral treatment strategy ( Table 5 ) and treatment outcomes can be monitored in the headache diary over time. Cognitive and behavioral sleep treatments described extensively elsewhere[87-89] are summarized below. Relaxation Training. As noted above, insomnia is associated with heightened physiological arousal. Relaxation training (ie, progressive relaxation training, EMG biofeedback, autogenic training), similar to common behavioral headache treatments, is widely employed in the management of insomnia and is particularly indicated when patients exhibit high physiologic, cognitive, or emotional arousal. Physiologic self-management skills are applied to decrease the waking state of arousal that is incompatible with sleep and thus facilitate sleep at night. Progressive muscle relaxation training directly targets physical tension, while guided imagery establishes a calm mental state in which patients may deliberately avoid intrusive arousing thoughts. Cognitive Therapy. In addition to physiological arousal, cognitive arousal including racing thoughts, worry, and intrusive thoughts is believed to impede sleep. Traditional cognitive therapy strategies like those utilized in stress-management for headache are employed to identify, challenge, and replace irrational beliefs and fears about sleep and sleep loss that provoke anxiety and play a role in the perpetuation of insomnia. Patients may be asked to self-monitor or solicit beliefs and fears about sleep, or otherwise complete a standardized questionnaire (eg, Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep[90]) to identify insomnia perpetuating cognitions. Patients reporting racing or obsessive thoughts around bedtime, and catastrophizing or ruminative worry about sleep are candidates for cognitive therapy. Techniques are taught to challenge dysfunctional fears and restructure rational statements that the patient will apply when the dysfunctional thought or emotional state occurs. Cognitive therapy is also widely used in behavioral headache treatment as well as in the treatment of affective disorders. Stimulus Control. Based on operant conditioning principles, stimulus control aims to reinforce associations between the "state of sleepiness" and the sleep environment. Patients are instructed to remain in bed only when sleeping and are advised to physically remove themselves from the sleep environment when they are unable to sleep. Over time, the bedroom environment becomes powerful discriminative stimulus for sleep. These strategies are effective for both sleep onset and maintenance insomnia, and may be delivered in 5 simple rules:

Circadian Rhythm DisordersThese conditions are defined by an alteration in the timing of sleep. In delayed sleep phase syndrome, for example, patients are unable to fall asleep at the desired (normal) time such as 10:00 AM or midnight. Their body clock allows only for sleep too late (delayed), such as 4:00 PM, resulting in difficulty getting up at the desired time (6:00 AM or 8:00 AM) and morning sleepiness. Other circadian (or phase) conditions include advanced sleep phase syndrome, jet lag, and irregular sleep-wake cycles. Clinical presentation can thus include sleep onset or offset insomnia, difficulty awakening at desired times, or daytime sleepiness. Treatment of phase disorders includes appropriately timed bright light and melatonin administration.[91]There is evidence that headache is a symptom of phase shifting, including shift work.[92,93] In our clinical experience, the most common scenario is an adolescent or young adult with delayed sleep phase combined with morning headache and complicated by morning light avoidance. Studies suggest that headache is not only a symptom of phase changes, but that ingested melatonin can be helpful for both the sleep disorder and the headache. Melatonin is a pineal-released hormone which transduces environmental light to a biologic signal, thus mediating seasonal reproductive behavior. Its role in humans is unknown, but it has proven therapeutic value in some circadian rhythm disorders. It is only a weak hypnotic. In addition, there are several studies that suggest melatonin treatment can improve headache syndromes even in the absence of a phase disorder.[94] Further studies are needed to define appropriate doses and timing of administration in specific conditions. ConclusionsSleep disorders have been associated with more frequent and severe headache. The most notable conditions include OSA, primary insomnia, and circadian phase abnormalities. Treatment of the sleep disorder, especially sleep breathing disorders, can improve and in some cases resolve headache by removing a physiologic trigger for headache. Sleep disorders, especially insomnia, may overlap or coexist with psychiatric disorders such as depression or anxiety that portend a poorer headache prognosis and warrant attention. Thus, screening, evaluation, and treatment of sleep disorders in patients with chronic headache are warranted.Headaches proximally related to sleep (during the sleep phase or upon awakening) raise suspicion of sleep disorders. OSA particularly has been associated with awakening headache patterns presenting as migraine, tension-type, cluster, and unclassifiable headaches, and garners attention because of the potential for improvement in headache with treatment as well as the significant cardiovascular and other health implications. Though not yet examined in the headache patient, there is now recognition of a spectrum of sleep-disordered breathing (eg, UARS) that may help account for the established relationship between chronic headache and snoring in the absence of traditional risk factors for OSA. Pharmacologic and behavioral sleep regulation strategies for insomnia and circadian rhythm disorders are compatible with primary headache treatment. Behavioral treatments for headache can be readily expanded to assess and treat insomnia with procedures such as headache/sleep diary, progressive relaxation training, and sleep hygiene. Pharmacologic treatment of primary insomnia is likely to improve headache, but little clinical evidence is available for specific recommendations. The agents used for insomnia are appropriate in headache populations, and include benzodiazepine receptor agonists, anti-depressants, and membrane stabilizing agents (anti-convulsants). AppendixInstructions for Daily Headache Self-Monitoring FormSelf-Management Training Program for Chronic Headache. These forms are designed to help you keep a careful record of your: daily headache intensity levels, stress, disability, medication use, meal pattern, sleep (pattern, quality, amount), basal temperature (women only), and menses (women only). Each page contains 7 grids—1 for each day of the week. You may want to fold the sheet so you can carry it with you in your pocket or purse. Each grid has several spaces running horizontally that correspond with times of the day (12:00 AM to 11:00 PM) for each day of the week. These boxes will be used to keep track of headache intensity, disability, stress, sleep, and meals. On top of the page are rating scales for headache intensity, disability, stress, sleep amount, and sleep quality. There is a large box at the top of the front page for listing medications that you take weekly. There are also boxes for keeping track of daily medications that are not used regularly. And finally, there is space available for making daily comments on any day of the week.We would like you to rate each day's headache intensity, disability, and stress at least 4 times each day. Most people find it easiest to make ratings at the same times each day. People also find it helpful to pair the act of recording with some other daily event to help them remember to record. For example, you might record (1) at breakfast or when you first get up, (2) at lunch time or when you hear noon church bells, (3) at supper time or when you first get home from work or school, and (4) at bedtime or when your favorite evening TV show begins. If you should happen to forget to make a recording at your usual time, please fill in the grid just as soon as you remember. In addition, whenever you take medication for a headache, please indicate the amount and type of medication in the space provided for that day. Each time you update the grid put the ratings in the boxes that correspond to the time of day that you are rating. For example, if you are making ratings for 6:00 AM Monday, then indicate the level of your headache, disability, and stress in the boxes of the column for 6:00 AM Monday. Put the number in the box that best describes how you are feeling at that time. For headache intensity you will put a number from 0 (NO HEADACHE) to 10 (EXTREMELY PAINFUL HEADACHE), for disability level you will put a number from 0 (NO IMPAIRMENT) to 10 (COMPLETELY IMPAIRED), and for stress you will put a number from 0 (NO STRESS) to 10 (EXTREMELY STRESSED). Do not be overly concerned with the exact rating level you select; your first impression is probably the best estimate. If you have a day with no headache, please be sure to complete the grid anyway. To indicate your sleeping pattern, you will place an "X" in the boxes that correspond with times that you were asleep. If you slept for only half of the hour, then place a "/" in the box. For indicating meals and snacks, place an "X" in the hourly boxes that correspond with times of the day that you ate a meal or a snack. Also, once a day you will rate your sleep amount and your sleep quality in the single boxes to the right of each day's grid. When you rate your sleep amount, you will place the number corresponding to how much you think you slept from 0 (TOO LITTLE) to 10 (TOO MUCH). When you make this rating, we want you to tell us what you feel about your sleep amount, not how much experts tell you should have. For example, some people might sleep 8 hours, but still feel like it was too little. On the other hand, other people might sleep 8 hours and think it was too much. Additionally, you will rate your sleep quality by placing the number corresponding you your experience ranging from 0 (VERY POOR) to 10 (EXCELLENT). Example Form: Included with this appendix is an example. You can see that on Monday, Marcy reported NO HEADACHE (intensity 0) at 6:00 AM when she got up. At noon, she had a SLIGHTLY PAINFUL (intensity 2) headache, by supper time (6:00 PM) she reported a PAINFUL (intensity 6) headache, and just before bed (10:30 PM) it had decreased to SLIGHTLY PAINFUL (intensity 2). Her level of disability was the same throughout the day, MINIMALLY IMPAIRED (2) at 6:00 AM, 12:00 PM, 6:00 PM, and 10:30 PM. But, Marcy has a stressful job, so her stress level decreased after she came home from work. It started out as VERY STRESSED (8) when she awoke (9:00 AM) and remained high at noon. Her stress dropped by supper (6:00 PM) to SLIGHTLY (2) and she experienced NO STRESS (0) as she went to sleep (10:30 PM). To indicate that she awoke at 6:00 AM, she marked an "X" in the boxes corresponding to 12:00 AM, 1:00 AM, 2:00 AM, 3:00 AM, 4:00 AM, and 5:00 AM. She took a 30-minute nap at 7:30 PM, so she put a "/" mark in the sleep box corresponding to 7:00 PM. She fell asleep at 10:30, so she put a "/" mark in the sleep box for 10:00 PM, and an "X" in the sleep box corresponding to 11:00 PM. She ate breakfast at 7:00 AM, lunch at 12:00 PM, a snack at 3:00 PM, and supper at 6:00 PM. Therefore, she placed "X"s in the meal/snack boxes for 7:00 AM, 12:00 PM, 3:00 PM, and 6:00 PM. Upon waking, Marcy took her body temperature and found that it was 98.6°, so she indicated this in the box marked "TEMP." Since she was not menstruating on Monday, she circled the "N." Marcy also made a subjective rating of her sleep amount by putting a "3" in that box, indicating it was somewhat too little. She thought the sleep that she did get was FAIR, so she placed a "4" in the box for "SLEEP QUALITY." Marcy took 2 aspirin and 1 butalbital (50 mg) for her headache on Monday. She also noted in the comments box that her nap seemed to help reduce her headache intensity. When filling out each grid, please be sure to write your name and the dates of the week on each page. If you have any questions about these recording procedures, feel free to call and ask for advice.  Figure 5. (c) 2006, Jamie L. Rhudy, Ph.D., Donald B. Penzien, Ph.D., & Jeanetta C. Rains, Ph.D. Form accompanies the Self-Management Training Program for Chronic Headache: Therapist Manual Reproduced with permission of author (JCR). CLICK HERE for subscription information about this journal. Table 1. Brief Sleep Questionnaire (Reproduced with permission from author [JSP])Table 2. Epworth Sleepiness Scale (Reproduced with permission from Johns[55])Table 3. Norms of the ESS (Reproduced with permission from Johns[55])

Table 4. Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Signs and SymptomsTable 5. Behavioral Treatment Strategies Suggested for Insomnia Based on SymptomsReferences

Abbreviation Notes

IHS International Headache Society, DSM-IV Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Ed., OR odds ratio, ESS Epworth Sleepiness Scale, OSA obstructive sleep apnea, PLM periodic limb movements, UARS upper airway resistance syndrome, RERAs respiratory effort related arousals, CPAP continuous positive airway pressure

Reprint Address

Dr. Jeanetta C. Rains, Center for Sleep Evaluation, Elliot Hospital, One Elliot Way, Manchester, NH 03103

Center for Sleep Evaluation, Elliot Hospital, Manchester, NH (Dr. Rains); and Scripps Clinic Sleep Center, Division of Neurology, Scripps Clinic, La Jolla, CA (Dr. Poceta).

Dr. Rains is a member of the speakers bureau of Sanofi Aventis and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Poceta is a member of the speakers bureau of Glaxo Smith Kline.

|

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)